What Can We Do to Be More Interesting Than an Algorithm?

When college students come to my friend Eric Johnson for career advice, he gives them a challenge to solve: “Figure out something you can do that an algorithm can’t.”

It’s an important question to ask, but coming up with an answer is increasingly hard.

From its earliest days, technology has been sold as a solution to the repetitive nature of work. It’s not “worthy” of humans to do repetitive tasks; machines or programs can do them quicker and more efficiently. We need to reserve ourselves, we’ve been told, for the things that “only humans” can do. Then, with all the extra time we save by having technology do the boring stuff, we will be able to unleash a torrent of creativity.

There are at least three problems with the argument.

It’s hard to know how to prepare for a new world if you don’t know where the goalposts are.

1. The goalposts keep moving:

Everytime we lift up a set of things that technology can’t possibly do, we discover it can. We thought auto assembly was too precise for a machine to do, until machines got better than humans; that only bank tellers could do banking, until ATM’s; that only travel agents could book travel, til Expedia.

Then we declared that technology would never be able to play chess, file taxes, do legal research, perform surgery. And then it could.

But surely AI’s could never do anything “creative” -- produce new songs, make art, write fiction. Well, it keeps getting better.

The range of jobs that will be eventually be eliminated or dramatically changed by automation is laughably imprecise – somewhere between 9 and 47%, says the GAO – but there’s nothing to suggest that even the upper end of the estimate is high enough.

It’s time we accept that over the next 50 years, technology will relentlessly encroach on every piece of work we consider human beings uniquely skilled at, and all of us need to be prepared for change.

2. We suck at change:

It’s been “easy” for public policy makers to tell manufacturing workers or coal miners or cashiers or truck drivers to suck it up and find new things to do. “Most people are fine with change for other people, but struggle when they have to change themselves,” Audrey Loper, who works for the Collaborative for Implementation Practice at UNC-Chapel Hill told me during a recent conversation.

So instead we pretend it’s no problem. “Just retrain,” we say.

But there’s a reason “just” is a four-letter word. It ain’t that easy to abandon the familiar. It’s not only factory workers that don’t want to retrain; neither do lawyers or accountants or doctors or musicians: nobody wants to start over from ground zero. Not the loom operator who lost her job five years ago and not the truck driver who’ll lose it next year; not the software developer in five years and not the surgeon in ten. Most of us will fight with every fiber of our being to find a new job doing the same thing before we even consider “reinventing” ourselves.

3. We’re not accustomed to creating – or recreating – ourselves:

That’s because most of us lack the skills and the will to do massive reboots. A survey by GoBankingRates found that 42% of Americans have considered starting their own business, but only 6.7% (1 in 16 people) are actually operating one, and many of those small businesses are unlikely to survive the technology onslaught. If we look at “breakthrough” ideas, about 32% of Americans surveyed by Findlaw.com think they have a patentable idea, but only 1/10 of them have taken even the first step toward pursuing it. We can’t assess what percentage of those “great ideas” are actually great, but the numbers mean only 1 out of every 33 of us are even thinking about doing something patentable.

A lot of the public policy related to this challenge has been assuming the end result, as machines replace humans, will be massive unemployment. Sam Altman, the founder of Open AI, as well as many others, have been studying what it would take to implement Universal Basic Income, to help ensure that the millions of laid-off humans could continue to eat while they wait to find something valuable they can still do.

How can we avoid becoming the passive tech-addled sloths depicted in “Wall-E”?

But while UBI could be an important stopgap, we can’t afford to have a “Wall-E” style population disengaged from work and creation. We need to begin now to develop new skills to enable many more of us to adapt quicker and create better. Here are two starter ideas:

Adaptation #1: Learn how to “do” change better

It makes sense that humans would be bad at change. Until recently the pace of change was glacial, not exponential. But now whole industries are born, peak and die within a generation, new technologies are introduced and adopted nearly instantaneously. Current projections by the US Department of Labor are that the average American will have 14 different jobs by the age of 38.

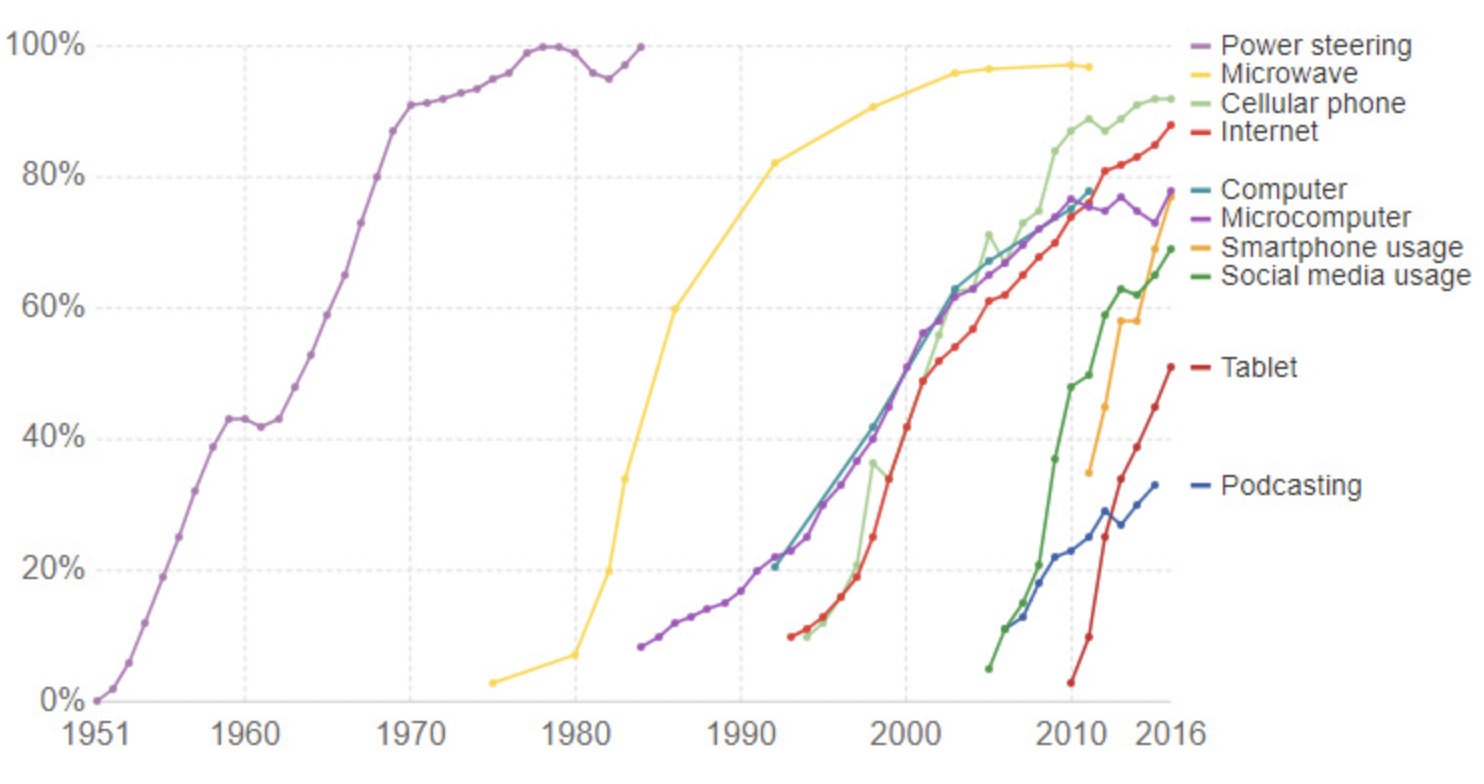

The speed with which we adopt technologies means we do many things more efficiently… and have to change jobs more often.(image from Visualcapitalist.com)

There’s a developing science of how we can “do” change better. We need to learn as much as we can about what works, and start teaching adults and young people how to adapt.

Adaptation #2: Increase our percentages of creators and entrepreneurs

A famous video in 2007 by Karl Fisch, a Colorado high school tech teacher, managed to put the challenge starkly: “We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist, using technologies that haven’t been invented, in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet.” Except we still aren’t really doing that. We need to get much better.

With knowledge of facts and routine processes increasingly handled by machines, our education system needs to reorient toward raising up people who know how to access information (think librarians) or people who are something closer to “T”-shaped (with a deep understanding of one subject but with a broad familiarity of other subjects) so that we can have more people able to make the kinds of leaps still only humans can.

It’s not that the US is lacking in its current ability to address big problems. The country currently ranks third globally (behind Switzerland and Sweden) in the annual Global Innovation Index, an attempt to measure “innovation” across 80 categories, including “technology outputs,” “creative outputs,” “business sophistication” and “human capital.”

But this is a bigger problem than we have had to face before. With the speed and scope of change that’s coming, dramatically more of us need to get much better. It can’t be 1 in 33.

References:

GAO estimates on impact of automation: https://www.gao.gov/blog/which-workers-are-most-affected-automation-and-what-could-help-them-get-new-jobs

GoBankingRates survey on starting a business: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/nearly-half-americans-considered-starting-140058309.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAJjaCTHzfgN5q2TFNXN4_gmwnLxGGMTZY60wof6E6HCL2LdQ46WKGIRlDv5V_M4dqG3CCYMFWgZ4l8_HUZ5XCx7l3gK5-1QGK3qRztnzISELy2BnLCALkRKkoHBxgtxs7TSCPPPVzfOOCemMsZJfAVDDcSRxyc1I1zmWGPUSKau-

Findlaw.com survey on “patent” ideas: https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/1-in-3-americans-invent-but-few-pursue-patents-findlaw-survey/

Better understanding change: https://hbr.org/2022/04/change-is-hard-heres-how-to-make-it-less-painful

“Shift happens” video: https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&rls=en&q=karl+fisch+shift+happens&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8#fpstate=ive&vld=cid:f2c887ba,vid:ljbI-363A2Q,st:0