D-Day, Dad’s Day and a Message to a Complaining Nation

Like a lot of people, I watched last week’s coverage of the anniversary of D-Day. The Allied invasion was the largest amphibious assault ever, with thousands of troops landing on the shores of northwest France to begin an effort to take back mainland Europe from German forces.

The stars of the ceremonies were the small number of survivors. Eighty years later, they looked somehow out of place, like nothing more than cute old men.

The survivors of World War II were forever shaped by the experience.

Most were in wheelchairs. They ranged in age from 98 to 104. But think what that means: in 1944, they were all 18-24 years old, asked to face the real possibility of death and to take on the responsibility of saving the free world.

This Father’s Day, I wanted to try to understand what it was like for veterans to have to shoulder that kind of burden. More specifically, I wanted to wrestle with how my father’s service in World War II shaped him, and what that might mean for the generations of us who followed.

I spent this week rereading some of the letters my father wrote home during the war. One in particular stood out.

Here’s some context. My father served in the Pacific, an Army engineer charged with building landing strips for planes in New Guinea and the Phillipines. Later he helped plan and build temporary bases in post-war Japan.

The letter and (clockwise left to right) a quiet moment with friends on New Guinea; in uniform with brother Charles prior to deployment; military ID.

The letter finds him in 1944, 24 years old, the same age as my twins are now. The battle to retake the Philippines from Japanese forces is still raging. He’s writing just after he’s dodged two bullets – actually two bombs – both of which could have killed him.

The first had come three days earlier. He watched a Japanese bomber level an area his unit had just evacuated. In this letter he speculates that even if he’d still been there, he probably would have survived, “cause I would have been safely nestled in a foxhole with my steel helmet.” Well, maybe.

The second bombing happened just a couple of hours before he starts writing. He had been asleep on board a ship transporting him between two Phillipine islands when a giant explosion lifted his boat out of the water, throwing him into a wall. When he makes it topside, he sees a giant cloud of smoke and a mile wide strip of debris. The ammunition ship behind his in the convoy has just been blown up and is sinking, apparently having killed everyone on board.

As he writes, an intense air battle has just concluded overhead, with the result of 59 Japanese fighters and bombers being shot down (the number of US planes lost was censored from the letter). My Dad is still shaken, trying to put what has just happened into perspective:

“On the sea there is, strangely enough, no place to dig a foxhole – you just wait and hope and pray (I think most of us do) that it is not your turn.

“Unconsciously you slip into your life jacket and steel helmet ...and then wonder is it this time – will they actually hit the convoy or are they just in the area – will they hit us? – they haven’t yet – thank goodness and God you say! Thanks for having gotten by the times before and hoping God will continue your good luck. Then you wonder – did I thank him for getting me so far along – yes I did but thanks again – and then you sit and wait, wondering if there is any precaution you should take that you haven’t.

“I don’t know what goes thru other guys minds but that is (what) happened in your little boy’s brain this morning. You think about all your loved ones and friends many times & the happy recollections of times past & are so glad that they aren’t with you at the time – because you don’t want anything to happen to them.

Then there’s this remarkable pivot, an attempt to minimize the whole thing, in an effort to reassure his parents:

“I say to myself I hope Mother and Daddy aren’t wasting any worry on me cause really everything is under control – nothing’s going to happen – and if I thought you were worrying I wouldn’t give you these frank thoughts & experiences that I have gone through. I wouldn’t write you anything but sugar-coated letters leaving out all of this but I know you aren’t worried – I know you’re concerned just as I am for you at home – but I know you are too good a soldiers to worry about my welfare.”

And then the letter takes another pretty amazing direction. He drops the whole subject and moves on. He speculates on what his sisters Mary and Sue and younger brother Bill might be doing. He wonders about his other brother Charles (who came ashore in Normandy three weeks after D-Day). He asks if his parents might consider buying him a subscription to Life Magazine for his upcoming birthday, and “maybe Reader’s Digest also.” Then he goes into an extensive description of Filipine building techniques and architecture, compares Filipine drainage techniques to US strategies and tells some stories about village life.

As a child I knew nothing about my father’s time in World War II – only that he had served in the Pacific – like a lot of veterans, he didn’t speak about it. Ever. We found this letter, and dozens of others, only after his death, in a footlocker he brought back from the war.

It’s hard not to see an early version of the man who would become my father pulsing out of this letter. And it’s hard not to see how those character traits have shaped me and my sisters throughout our lives.

See if any of these ideas resonate with you as you reflect on WWII veterans you may have known.

Don’t complain: I can’t remember my father complaining about anything he faced in my lifetime. Not business downturns; not colds or sicknesses or surgery; not death of loved ones; not bad weather; not even bad bounces on the tennis court. There can’t be anything more frightening than facing death and seeing suffering day after day; I suspect the war always gave him a reference point. My sisters and I grew up learning not to complain about our lives.

Hedge your bets: The war wasn’t the first tough test for my father’s generation: they’d grown up in the Depression, and my father watched his parents lose their home and scrape out a living. And it wouldn’t be the last test either. But the war was pivotal: I think it cemented a commitment to always prepare for the worst. Throughout his life, my father never borrowed: he waited to build our house till he could pay for it with cash. We grew up learning some of those same lessons. Never borrow beyond your means or get smug about your life. Enjoy it, because it can change in an instant.

Our country is something to be proud of: Like so many WWII vets, my father signed up as soon as war was declared. Throughout his war letters, there is a visceral pride in the cause and the country he was fighting for. I found a note he had made to himself in tiny script at the bottom of his foot locker: “We are soldiers fighting for peace… and when it comes, we will set ourselves to bringing peace to all.” That pride of country only grew after the war, and suffused our childhood. Regardless of who was leading our country at any given time, we were taught to be proud of where we lived – “the greatest country in the world.”

Write letters: Letters from home were clearly manna to my father and all soldiers in wartime – an escape to familiarity in a surreal world of strange bedfellows, new countries and imminent danger. He never forgot how those letters made him feel, and for the remainder of his life he was a compulsive letter writer, dropping people lines when they won awards or lost a loved one, but also when they stubbed their toe or when he just thought they might need encouragement. When I was away from home for the first time on my 16th birthday and feeling miserably lonely, he sent me 100 letters over the course of a few days; over the course of his lifetime, we estimated he had sent 15,000 letters. “It doesn’t take long to write someone a note,” he would say, “And it may be just what they need.”

Eighty years on from 1944, I marvel about how far our world has come, but I also worry about what we have lost. For 95% of us the world is dramatically safer than it was then. Life is fairer for huge swaths or the population. Our standard of living is shockingly higher. Unemployment is low; job growth is exploding; wages are rising faster than inflation. It’s easier than ever to travel, be entertained, to exercise, to live. But with no external enemy to fight we’ve gone to war with each other.

We are at once blindly optimistic, spending and borrowing way beyond our means, and painfully pessimistic, fixating on every flaw and forgetting all that we have. We’ve become a nation of malcontents – it’s not that there isn’t stuff to carp about; it’s that our default has become to complain, rather than do; to whine rather than fix.

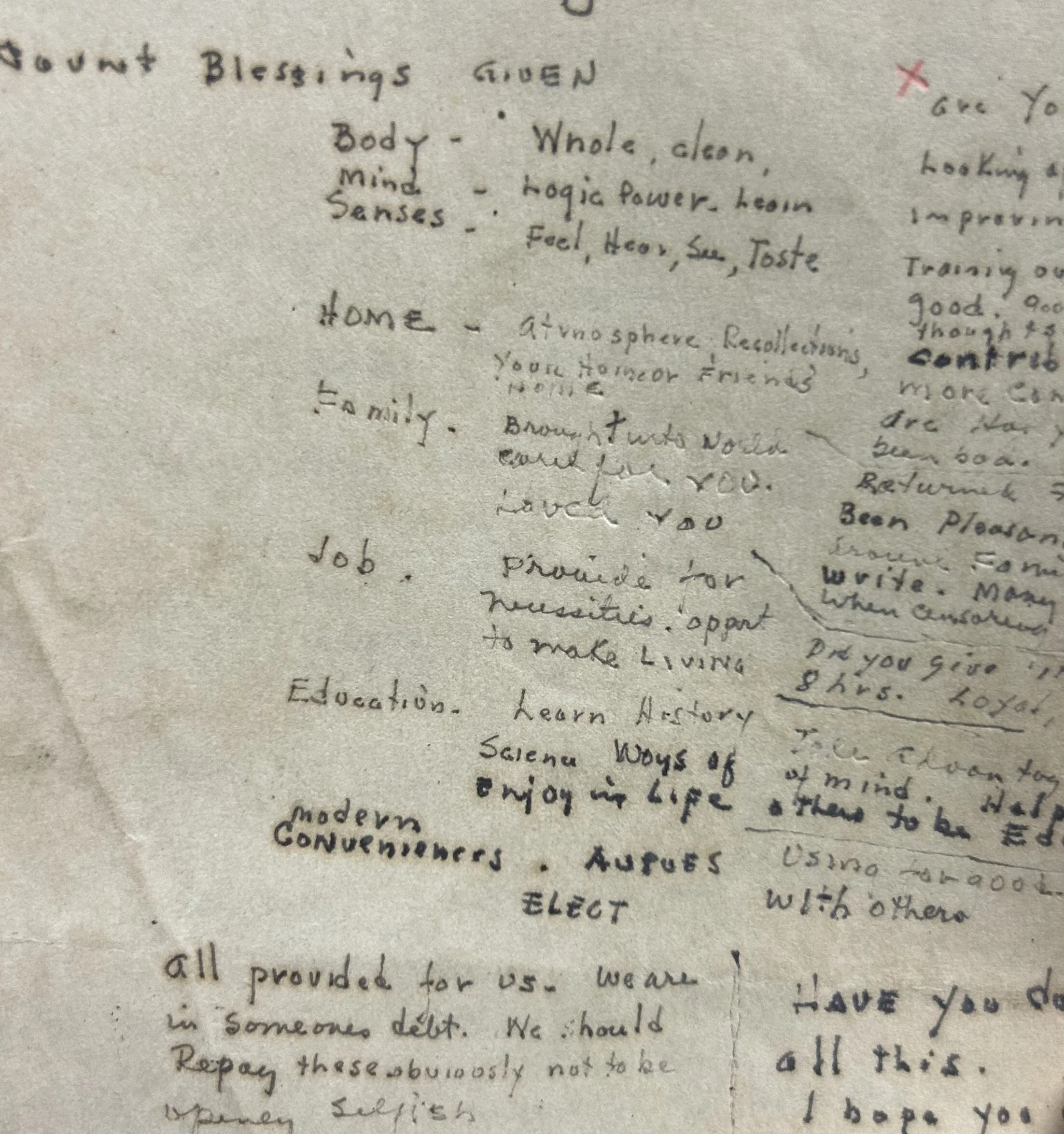

Here’s an antidote, part of another set of notes I found in my father’s foot locker, hand scrawled:

What really matters. 1944 edition.

“Use your good.

Share with others.

Count blessings given: body, mind, senses, home, family, job, education, modern conveniences.

All provided for us. We are in someone’s debt . We should repay these.

How have you shown your appreciation for all these things?”

Some items in the foot locker: photos from home, plans for base construction in post-war Japan, a mess kit, inspirational words….

This Father’s Day, four score years out from that other day, I hope we can remember the courage in the face of fear, the can-do spirit against ugly odds and the gratitude during deprivation of our fathers and grandfathers. Then I hope we can celebrate all that we have and commit to working to make our countries ever better, for us and for others. And maybe we’ll even make those few remaining 104-year-old’s proud of us.

Notes:

D-Day commemorations: https://apnews.com/article/d-day-france-russia-ukraine-wwii-7b6896a9d891fb2d2f75b29e1cfd67ad

The campaign to retake the Philippines, 1944-1945: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Philippines_campaign_(1944–1945)&diffonly=true

I