Fandom

At the end of our lives, there are probably about 5 moments we look back on that are so deeply engraved in our consciousness that we can’t forget them.

For me those will include some obvious ones that may match up with yours: standing on the altar watching as my soon-to-be wife walks down the aisle toward me; the birth of our children; the moment I heard the news I was getting a big job.

If you are a sports fan, you likely have at least one of those moments reserved for something your favorite team did.

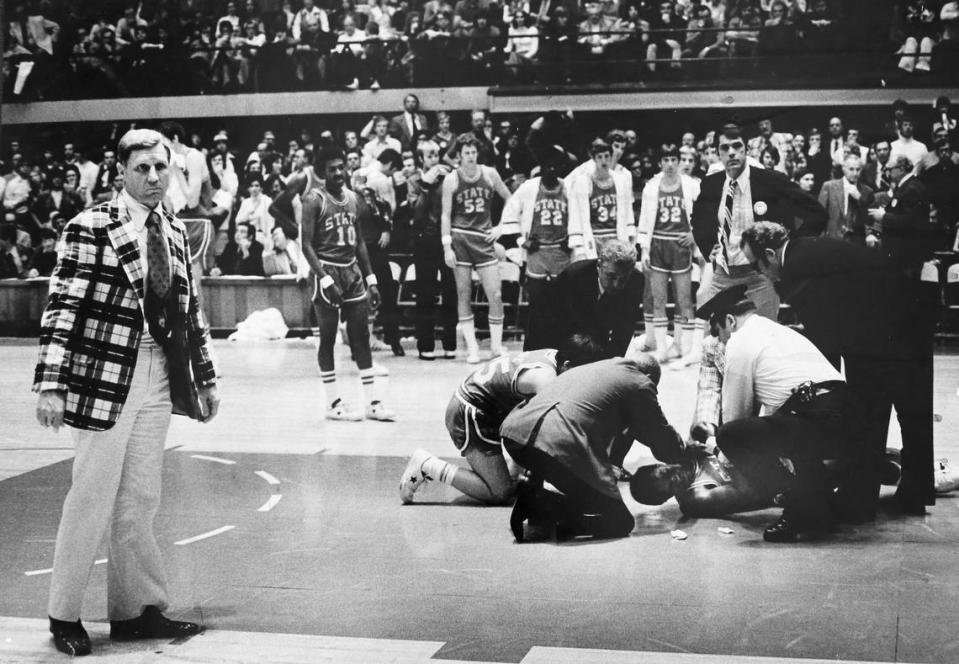

NC State Coach Norm Sloan can’t look as attendants try to help a fallen David Thompson, March 17, 1974.

Here’s mine. It was March 1974 and, by some miracle, my father had gotten tickets for the two of us to see my beloved NC State Wolfpack men’s basketball team play a sold-out home game against Pittsburgh in the 2nd round of the NCAA tournament. Midway through the first half, all 12,390 NC State fans (I’m just guessing there were 10 Pitt fans there, though I never heard them) could see it was NOT going well, and there was a real chance that a dream Wolfpack season would come to an end. That’s when my childhood hero, David “Skywalker” Thompson, says he decided he needed to do something to turn the game around – he would block the next Pitt shot no matter what. As the shot went up, Thompson took off from the free throw line and swatted the ball away. But he caught his foot (his foot!) on the shoulder of his teammate, 6’9” Phil Spence. He went down hard – very hard — and it was like someone had hit the mute button on the arena as he was carried off, unconscious, on a stretcher. Nobody said it out loud, but we really thought he might be dead (I found out later that news icon Walter Cronkite had been standing by in the CBS newsroom to cut in with the news if Thompson had died).

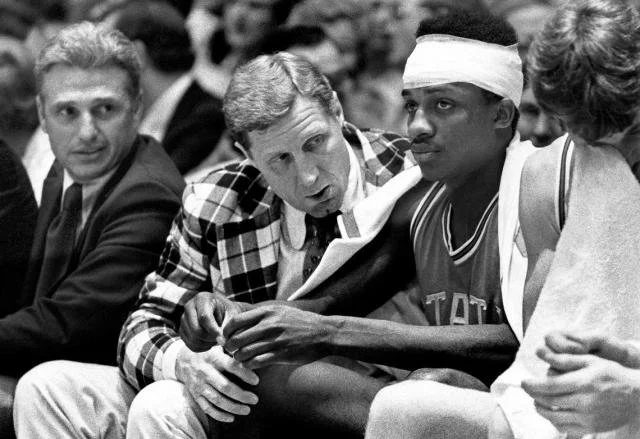

But that’s only half of the moment for me. The other half came with eight minutes left in the game when David Thompson walked (he could walk!) back in the building, his head encased in a four-inch wide band of gauze wrapped like a turban over 16 stitches, smiling (he could smile!). Teammate Tommy Burleson, who was shooting a free thrown at the time, dropped the ball and jogged over to hug his friend and the game stopped cold as everyone in the building stood up and started screaming – creating such a wall of sound that I remember vibrating.

Was it joy? Relief? Shock? I know I cried. I side-hugged a stranger beside me (the high five hadn’t been invented yet) and front-hugged my Dad like I hadn’t since age 2.

And then he was back! David Thompson returned from the hospital to see his team beat Pittsburgh, then led the team to the NCAA Championship two weeks later.

And I was there. I saw that. And I felt that. I was part of something really big and joyous and shared — and ecumenical. As a Wolfpack fan that day it didn’t matter that David Thompson was black and Tommy was white, and I would have hugged the stranger beside me if he was rich or poor, gay or straight, male or female, Republican or Democrat, Christian or Wiccan, from Russia or Raleigh, because we shared something: a love for that player and that sports team. And no other difference outweighed that.

It's been a long time since I’ve had that sort of feeling. The Wolfpack basketball team won a national championship again a few years later, but I was living in Virginia and there was nobody else around to celebrate with. Amherst College, where I went to school, won two Division 3 national basketball championships, but the fan base for Amherst could most generously be described as an “enclave”— there wasn’t the same feeling of being part of a larger, sprawling, diverse, amorphous “nation.”

And then there was the moment last month when Wolfpack Nation howled back to life.

On March 16, 2024, exactly 50 years after the Pittsburgh game, the men’s basketball team completed a 5-game sweep of the other teams in the ACC and earned a spot in the NCAA Tournament. The wonen’s team went on their own run. I spent the next three weeks as a proud citizen of a suddenly rejuvenated fan base, watching the women’s basketball team overcome long odds to make the NCAA Final Four, and the men’s basketball team make what bustinbrackets.com described as “the most improbable run in NCAA Tournament history.”

I busted out my red and white zips and pullovers. I shared conversations with strangers about obscure team trivia (“Did you know Saniyah Rivers is from my hometown of Wilmington, NC?” “No I don’t know DJ Burns’ ‘real’ weight – what do you think?” “I have a friend who lives next door to DJ Horne”). My wife and I went to viewing parties for both teams. I had a nightmare about Purdue’s giant player, Zak Edey. Even friends who are die-hard fans of other schools were nice to me.

I counted 83 people in line at the “NC State Store” buying merch the day before Final Four weekend.

This Wolfpack watch party at a bar across from campus spilled over into a nearby street.

And then within 25 hours both dreams ended. Two freakishly good giants – a 6’7’ woman from Brazil playing for South Carolina and a 7’4” man from Canada playing for Purdue — snatched Cinderella’s slippers and snuffed out the Pack miracle.

There are some quantifiable positive side effects to having “your” team do well. Research shows that the success of “your team” correlates with improved mental health outcomes. There is clear evidence that applications to successful college sports teams’ schools increase the year following their success. Alumni donations may even go up marginally.

But I wasn’t thinking about any of that during the Pack’s run. It was just cool, for a few days, to be part of something unabashedly positive, and to be able to share that bond with everyone from checkout clerks to preschoolers to farmers to bioengineers. We don’t have to have attended the school (I didn’t) or know the players (I don’t); instead we have opted-in to support that team, and the opters-in are a range of people I don’t find with book or band or food or fitness or faith fans.

But now I and the other members of Wolfpack nation return to our “normal” lives, the ones where we segregate ourselves into homogenous groups living behind walls or gates. We cloister ourselves economically, politically and racially: in our neighborhoods; in our friend groups; to some extent in our workplaces; to an even greater extent in our religious lives. These days we can’t even come together on the question of whether we want to live in the same country — 23% of us want our states to secede from the Union.

How hard would it be for us to find some common ground across those lines? And is sports really the only gateway we can find?

Notes:

David Thompson’s great fall: https://gopack.com/news/2008/8/11/Remembering_Reynolds_David_Thompson_s_Great_Fall#:~:text=Somewhere%20near%20the%20top%20of,when%20he%20hit%20the%20ground.

The “Flutie” effect on college applications: https://www.ivywise.com/blog/the-flutie-effect/

Review of impact of athletic success on student quality and donations: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7072/7/2/19

Impact of negative team outcomes on mental health: https://www.npr.org/2022/02/14/1080684282/what-it-means-for-sports-fans-mental-health-when-their-team-loses

Other mental health impacts of sports viewing: https://fherehab.com/learning/benefits-spectator-sports

What we get through being part of a fan group: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7225319/

Secession polling: https://www.newsweek.com/map-shows-states-most-likely-secede-1870679